Auto-vectorization for the Masses (part 5 of n) - Code Generation, Graphs and A-star

by Andre Leiradella

BackPart 5 of the series, you may want to read the previous articles before this one:

- Auto-vectorization for the Masses (part 1 of n): SimpleC and Abstract Syntax Trees

- Auto-vectorization for the Masses (part 2 of n): Construction of the AST

- Auto-vectorization for the Masses (part 3 of n): Semantic validation of SimpleC Programs

- Auto-vectorization for the Masses (part 4 of n): Optimization

Introduction

I’ve been writing the code generation part of the SimpleC compiler, but it has proven to be much harder than I anticipated. While writing code generation for the AddExpr, I had to edit the code multiple times to get it right. For the SPU there are five possible outcomes for the generated code:

d = si_fa( a, b )ifaandbare floatsd = si_a( a, b )ifaandbare integersd = si_ai( a, b )ifais an integer andbis an integer constant in [-512, 511]d = si_sfi( a, b )ifais an integer andbis the 512 constantd = si_fma( a.left, a.right, b )if at least one ofa, andbis of typefloatandais aMulExpr

It may seem easy to code these three rules to generate the correct outcome but there are other factors that make it hard:

aandbcan have different types. We have to cast the one which is an integer to a float and produce asi_fa- If

ais an integer andbis a float constant with an integer value but outside of the natural [-512, 511] range, which one is better: assemble an integer constant with the same value ofb, addato that constant (si_a) and cast the result to a float (si_csflt), or assemble a constant from the value ofb, castato a float (si_csflt) and add the two floats (si_fa)? - We have to test for

abeing an integer constant in [-512, 511] and usesi_ai( b, a )if b is an integer - If

aand/orbis aMulExprwe have to produce asi_fma, but only if the resulting type is a float - We want to produce the sequence of instructions with the smaller cost possible

And the list goes on. It’s true that some items on that list are easy to implement, but writing generating code for AddExpr bothered me enough to look for alternatives. One that looks promising is using graphs and [A](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_search_algorithm). I haven’t implemented to whole thing yet, but I want to share what I’m thinking of doing here and hopefully get some feedback.

Code Generation as Data Transformation

Consider the AddExpr class in the SimpleC source code. It has two operands of type Node and must output a Variable that is the identifier that holds the result of the addition. So the question we’re trying to answer is “how can we transform a tuple <Node, Node> into a Variable such that the resulting variable has the sum of the elements of the tuple?”

So I thought I could write a set of rules describing data transformations and let the computer figure out the best outcome each time AddExpr (and any other AST node for that matter) is compiled. The idea was born.

Data Transformation as a Graph

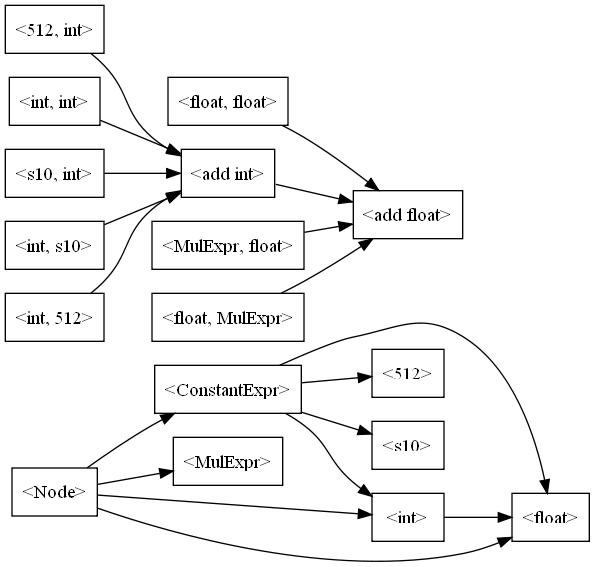

The first thing we need is some way to represent the set of rules describing the possible transformations of data. Constraining ourselves only to the subset necessary to compile a AddExpr node, we can build a graph like this:

The transformations’ constraints are as follows:

- From <

Node> to <int>: the type ofNodeisType.INT32 - From <

Node> to <float>: the type ofNodeisType.FLOAT32 - From <

Node> to <MulExpr>:Nodeis an instance ofMulExpr - From <

Node> to <ConstantExpr>:Nodeis an instance ofConstantExpr - From <

ConstantExpr> to <s10>: the type ofConstantExprisType.INT32, and its value fits in a signed 10-bit integer - From <

ConstantExpr> to <512>: the type ofConstantExprisType.INT32, and its value is 512 - From <

ConstantExpr> to <int>: the type ofConstantExprisType.INT32 - From <

ConstantExpr> to <float>: the type ofConstantExprisType.FLOAT32 - From <

int> to <float>: the type ofNodeisType.INT32 - From <

MulExpr,float> to <add float>: at least one operand ofMulExpris of typeType.FLOAT32 - From <

float,MulExpr> to <add float>: at least one operand ofMulExpris of typeType.FLOAT32

Transformations also have a cost associated to them. For example, going from <int> to <float> costs 7, the cost of si_csflt. Some transformations don’t cost anything and only serve to change the meaning of the data, as from <Node> to <512>.

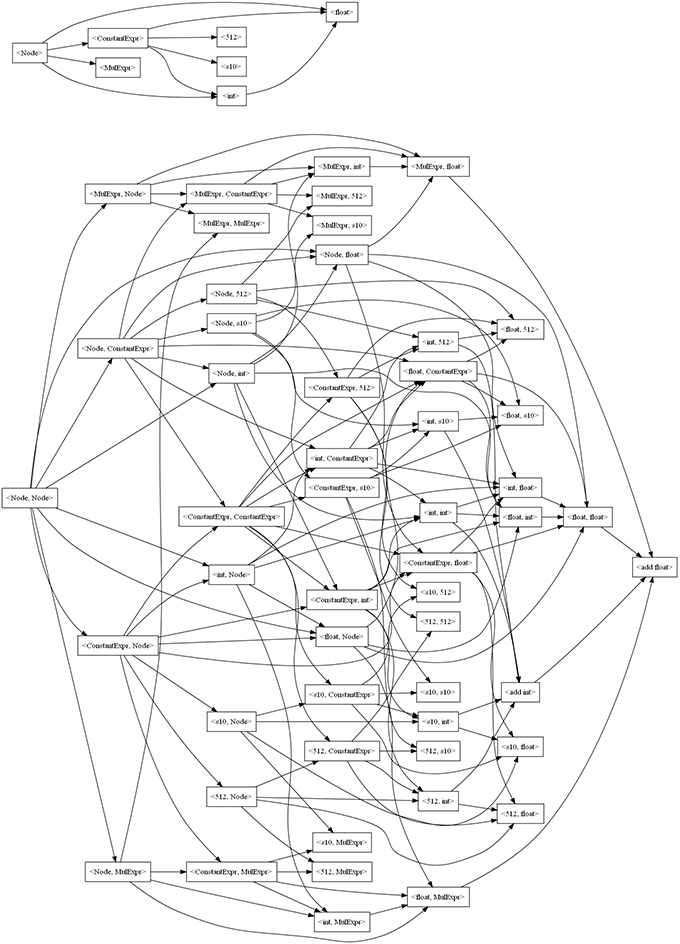

There’s a problem with this graph though. It’s impossible to start with <Node, Node>, the two operands for an addition in the abstract syntax tree, and arrive at an addition. That node isn’t even in the graph! We could add it and, by combining transformations of <Node> to other nodes, build other nodes and edges that would allow us to arrive at <add int> or <add float>. But it would be painful to do this by hand, so instead we write some code that takes a <Node, Node> and it builds all these nodes for us, which results in the following graph:

Ugh, good thing we let the computer do the work for us. It’s worth noting one thing though: there aren’t transformations that act on both types at the same time. For example, there isn’t a transformation from <int, int> to <float, float>. This is because the same thing can be accomplished via a transformation from <int, int> to <float, int> and from it to <float, float>, and the cost would be the same anyway but this way the node count is smaller.

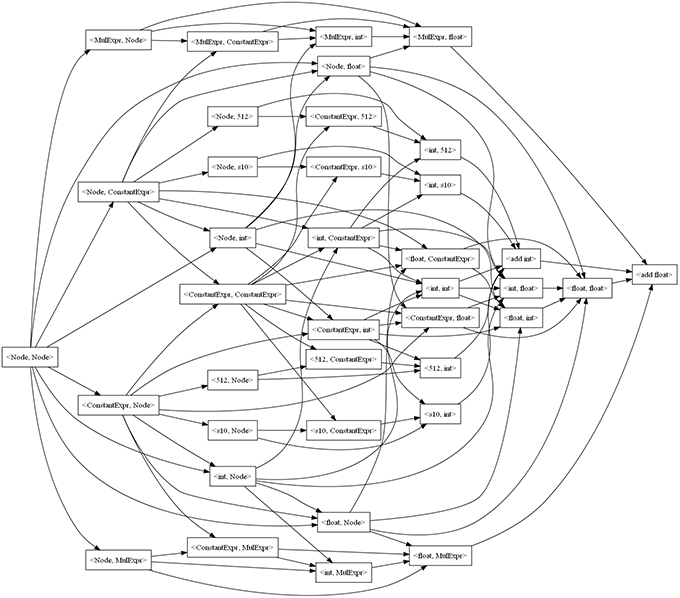

To shrink to graph a little, we can get rid of nodes which don’t have paths to the target nodes, <add int> and <add float>, since those are the ones we have to reach to perform the addition. Doing this (using the distance matrix from the next section) leads us to our final graph:

Code Generation as A*

With our graph in place all we have to do is give A* the start node <Node, Node> and one of the goal nodes, and voilà, our code is generated! Great, so we’ll have to code A*, which is easy, and the heuristic function, which is also easy… or it’s not?

A* is largely used for path finding, meaning that nodes are spatially positioned in relation to each other like in a map or maze. In those cases, implementing the heuristic is straightforward: for the former the Euclidean distance can be used, and for the later the Manhattan distance is a better fit if only axis-aligned movements are allowed. Unfortunately none of those fits in our case; our nodes cannot be spatially positioned like that and the actual cost of an edge depends on the path to the current node so far.

For A* to find the best path in the graph, the heuristic must be an admissible heuristic. In short, the heuristic from node x to node y must never overestimate the actual lowest cost to go from x to y. So we have two things to consider if we are to build an admissible heuristic for our graph:

- Some of our edges have constraints, which are conditions that must be satisfied before the edge can be taken

- Some of our edges have variable costs which depend on the data at the current node being considered in the search

The constraints are easy to deal with. If an edge has a constraint that is not satisfied at some point of the search, we can look at it as having an infinite cost. On the other hand, if the constraint can be satisfied the edge has its actual cost to be traversed. Since the heuristic must be admissible, we take the lower of these two values which is of course the actual edge cost.

The variable cost is not hard also. If it’s variable how can we be sure we’re not overestimating it? An easy answer for it is to consider the cost as zero, but it makes the search slower. What we need is the actual minimum cost for the edge, and we know it for all edges. For example, going from <Node> to <int> means a constant must be built for the integer value of Node. The minimum cost for building a constant is 2 (using si_il or another similar constant-formation intrinsic.) Some integers will require two instructions or one odd-pipe instruction with a cost of 4 but since we’re looking for the minimum cost we can take that as 2 for this case. So we can have the minimum cost of an edge as one of its attributes and use it for the heuristic if the actual edge cost is variable.

Another thing to consider is how we can evaluate the heuristic. It must not overestimate the actual cost, and the actual cost is the cost of the cheapest path so it seems we have to find the cheapest path between two nodes to get the heuristic right, which wouldn’t work since we’d be using A* to evaluate the heuristic for the A*. If that was the case we’d be better off using a breadth-first search.

To be able to evaluate the heuristic we can use the Dijkstra’s algorithm for all nodes and build a distance matrix. Here’s one column of the matrix showing the minimum cost to get from all nodes to the two target nodes:

| Source Node | Distance to <add int> |

Distance to <add float> |

|---|---|---|

<Node, ConstantExpr> |

4 | 8 |

<add float> |

- | 0 |

<MulExpr, float> |

- | 6 |

<int, int> |

2 | 9 |

<int, s10> |

2 | 9 |

<int, float> |

- | 13 |

<MulExpr, Node> |

- | 8 |

<ConstantExpr, float> |

- | 8 |

<s10, Node> |

4 | 11 |

<Node, Node> |

4 | 8 |

<add int> |

0 | 7 |

<float, ConstantExpr> |

- | 8 |

<Node, 512> |

4 | 11 |

<Node, int> |

2 | 9 |

<int, ConstantExpr> |

2 | 9 |

<ConstantExpr, ConstantExpr> |

4 | 10 |

<int, 512> |

2 | 9 |

<int, Node> |

2 | 9 |

<float, float> |

- | 6 |

<ConstantExpr, 512> |

4 | 11 |

<512, Node> |

4 | 11 |

<float, Node> |

- | 6 |

<MulExpr, int> |

- | 13 |

<float, MulExpr> |

- | 6 |

<Node, float> |

- | 6 |

<int, MulExpr> |

- | 13 |

<512, int> |

2 | 9 |

<ConstantExpr, s10> |

4 | 11 |

<Node, MulExpr> |

- | 8 |

<512, ConstantExpr> |

4 | 11 |

<ConstantExpr, int> |

2 | 9 |

<s10, int> |

2 | 9 |

<float, int> |

- | 13 |

<s10, ConstantExpr> |

4 | 11 |

<ConstantExpr, MulExpr> |

- | 8 |

<ConstantExpr, Node> |

4 | 8 |

<Node, s10> |

4 | 11 |

<MulExpr, ConstantExpr> |

- | 8 |

It’s interesting to note that not all source nodes arrive at <add int>, but all of them arrive at <add float>. This is because we have edges from <int> to <float> and from <add int> to <add float> so if it’s possible to arrive at <add int> it’s also possible to arrive at <add float>.

Well, with our graph and search algorithm in place we can finally start generating code. Well, almost. There’s still one problem: how do we dynamically evaluate edge constraints and variable costs? We’re lucky because there’s already a library that does exactly this, evaluates Java source code contained in strings: BeanShell.

Evaluating Constraints and Costs

I didn’t code this part yet, but I’ve used BeanShell before and it delivers on its promises. I can’t see anything that would prevent us from evaluating constraints and costs which is the last barrier to have actual generated code. I’ll keep working on this line and hopefully have something to write about in a month or so (no promises though!)

Conclusion

This has been a lot of work, but I strongly believe it’ll prove to be a huge time saver considering the amount of work I had with AddExpr. But there are many more benefits:

- We don’t have to write the same code twice.

SubExpr, for instance, would be very similar toAddExpr, and many transformations are already in place and won’t have to be coded again - We don’t have to write any code at all! I mean, after putting things in place, compiling another type of node will be just a matter of adding the necessary transformations to the graph

- It’s very easy to add more transformations that lead to more optimizations, such as from <

ConstantExpr> to a power of two integer and generate code forMulExpras left shifts - The computer is much better for finding the best path in a graph than we are, so I expect that the generated code will be better. We have to give it the correct transformations though…

- Targeting other architectures are easier, it’s just a matter of writing the transformations and feed them to the engine

I’m also excited with the possibilities:

- Transformations from <

ConstantExpr> to either <int> or <float> will be done by calling a method that builds the actual constant using constant-formation intrinsics. But I think this process should be part of the path finding, not only because the A* will figure out the best way to build the constants, but because there are possibly good optimizations such as integer multiplication when one factor is a constant with some properties (like the upper 16 bits being zero.) - By adding the right transformations I believe optimizations using intrinsics like

si_nand,si_norandsi_andcwill automagically emerge - If we add methods to query what code has already been generated, we could have transformations using the odd pipe to reduce the cost of the code

- Who knows what we can accomplish after adding all nodes that are arithmetic operations? Instead of compiling each node separately, we could feed the search with an <

Expression> and let A* figure out the best code for the entire expression! - What about adding all nodes from the AST? Think of global optimization, automatic inlining of functions… Ok, now I’m just on a trip now. I don’t really believe these kinds of things are possible without a higher-level coordination of the code generation process

Thanks for reading so far. Please use the comments section below and give me some feedback. Tell me what’s right and what’s wrong with this approach to code generation. Tell me what more it can accomplish or point me to a fundamental flaw in my train of thought that will kill it. Either way, thank you!

See ya!

Back