Auto-vectorization for the Masses (part 2 of n) - Construction of the AST

by Andre Leiradella

BackIn my my previous post we saw the grammar of the language we’ll use to write code for vectorization, SimpleC. We also saw what an Abstract Syntax Tree is and for what we’ll be using it. In this post we’ll learn how to build ASTs for inputs written in SimpleC and it hopefully will make it easier for us to visualize the opportunities for optimization and auto-vectorization which will help us move towards our goal.

Constructing the Tree

The AST for a given input written in SimpleC will be constructed during the parsing of that input. So while we parse, we’ll create different types of nodes and connect them together to form the tree. If you’ve checked the Wikipedia entry on ASTs then you already know that we’ll have one node for each grammar production, and you are almost right. Some productions are just helpers like type and id and some can be represented by just one node type such as the ones used to create constants so the relation between productions and nodes is not exactly 1:1.

Let’s begin writing our Node class. It will be the parent class of all nodes in the AST, and we’ll add a couple of methods that all nodes will need:

package com.leiradella.sv.ast;

import java.io.ByteArrayInputStream;

import java.io.ByteArrayOutputStream;

import java.io.ObjectInputStream;

import java.io.ObjectOutputStream;

import java.io.Serializable;

public abstract class Node implements Serializable

{

public String getUid()

{

return toString().replace( '.', '_' ).replace( '@', '_' );

}

public Node dup()

{

try

{

ByteArrayOutputStream baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream();

ObjectOutputStream oos = new ObjectOutputStream( baos );

oos.writeObject( this );

oos.close();

baos.close();

byte[] buffer = baos.toByteArray();

ByteArrayInputStream bais = new ByteArrayInputStream( buffer );

ObjectInputStream ois = new ObjectInputStream( bais );

Node node = (Node)ois.readObject();

ois.close();

bais.close();

return node;

}

catch ( Exception e )

{

return null;

}

}

public abstract String toDot();

}

getUid returns an unique identifier for the node, and dup returns a clone of the node. toDot returns a string containing dot code representing the node so we can plot nice AST graphs using Graphviz. Maybe we’ll need more things in our AST for optimization and code generation but for now those methods will suffice.

I won’t put all the source code here (you can download it here) but let’s see how the Function node is implemented:

package com.leiradella.sv.ast;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class Function extends Node

{

private String name;

private Type type;

private boolean isStatic;

private boolean isInline;

private List< Node > children;

public Function()

{

super();

name = null;

type = null;

isStatic = false;

isInline = false;

children = new ArrayList< Node >();

}

public String getName()

{

return name;

}

public void setName( String name )

{

this.name = name;

}

public Type getType()

{

return type;

}

public void setType( Type type )

{

this.type = type;

}

public boolean isStatic()

{

return isStatic;

}

public void setStatic( boolean isStatic )

{

this.isStatic = isStatic;

}

public boolean isInline()

{

return isInline;

}

public void setInline( boolean isInline )

{

this.isInline = isInline;

}

public void addStatement( Node n )

{

children.add( n );

}

public String toDot()

{

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

sb.append( getUid() ).append( " [ shape = record, label = \"{Function|" );

sb.append( "name: " ).append( name );

sb.append( '|' ).append( "type: " ).append( type );

sb.append( '|' ).append( "isStatic: " ).append( isStatic );

sb.append( '|' ).append( "isInline: " ).append( isInline );

sb.append( "}\" ];\n" );

for ( Node n: children )

{

sb.append( n.toDot() );

sb.append( getUid() ).append( " -> " ).append( n.getUid() ).append( ";\n" );

}

return sb.toString();

}

}

A function has a name and type and can be static and/or inline so these properties become properties of the Function node. Functions also have statements so we add a list of nodes as a property. I’m not a big fan of always making all properties private and add accessors, but it makes sense here because of the way nodes are created and populated as we’ll see later.

Apart of the accessors we only have the toDot method. It generates a node in the dot language for the function with all its attributes, generates dot code for all its children and connects them all with arrows from the function to the children. All other nodes are implemented similarly.

Ok, all is well but how and where are nodes instantiated and added to AST? We already know it’s inside the parser, but since the parser is generated how we can add code to it? The answer is what Coco/R calls Semantic Actions. It’s really just code that you add to the grammar and is output as-is along with the code Coco/R generates. Let’s see the function production with semantic actions added to it:

function< out Node n > (. Function f = new Function(); n = f; Type t; String i; Node o; .) =

[

"static" (. f.setStatic( true ); .)

]

[

"inline" (. f.setInline( true ); .)

]

type< out t > id< out i > (. f.setName( i ); f.setType( t ); .)

'('

[

argDecl< out o > (. f.addStatement( o ); .)

{

','

argDecl< out o > (. f.addStatement( o ); .)

}

]

')'

(

compoundStmt< out o > (. f.addStatement( o ); .)

| ';'

)

.

The first thing we can notice is that function is now followed by < out Node n >. This tells Coco/R that this production returns a Node to productions that use it. After the return type but before the equals sign we have code that will be added to the parser just before any generated code. In our case, this code is used to declare and initialize some variables: we instantiate a Function object and set n – our return variable – to this instance. We then declare t to get the function’s type, i to get the function’s name and o to get arguments and statements.

The first part of the production is the optional static keyword, and we set the isStatic property of the function to true if it’s present in the source code. The same thing goes for the inline keyword. After those we get the type and name of the function and set the respective properties. We then match a '(' and for each argument we add it to the function, the same happening to statements unless the argument list is followed by an ';' which means a function declaration instead of definition.

There is one more change we must make to have the generated parser return the AST. Even if our main production (SimpleC) is tagged with a return type the generated parser won’t return the value to the calling code. So we have to change the Parser.frame file, which is a template Coco/R uses to generate the parser, in order to make the Parse method return the AST root node:

public Object Parse() {

la = new Token();

la.val = "";

Get();

Object result =

-->parseRoot

return result;

}

Now we can take the return value of the Parse method and do whatever we want with it. One last change we have to make in order to have Coco/R generate the parser inside the com.leiradella.sv.parser.simplec package is to add a file named Copywrite.frame in the same directory from where it pulls the Scanner.frame and Parser.frame files. This file is added to the beginning of the generated scanner and parser so we just add package com.leiradella.sv.parser.simplec; to it. Coco/R has a command line option to specify the package of the generated files but it outputs it to the parser only, leaving the scanner on the default package.

Visualizing ASTs

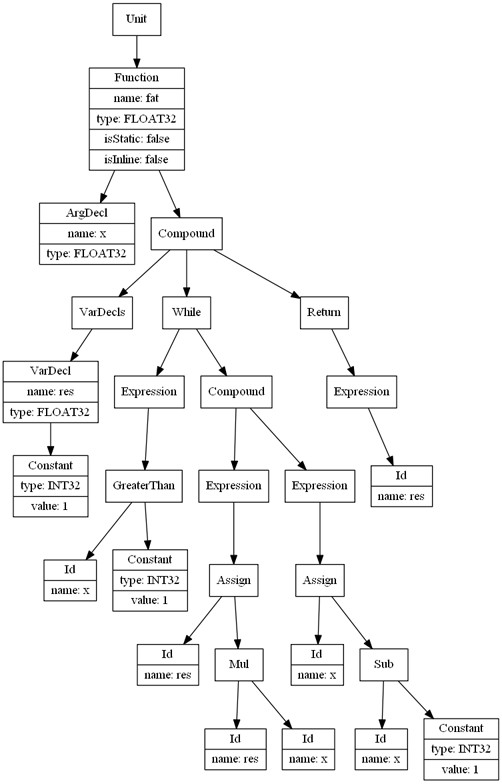

Let’s run the parser over some SimpleC programs and take a look at the resulting ASTs. To do this we’ll call the toDot method of the root node and output it to System.out so we can pipe it to dot. Everything is already implemented in the downloadable source code. Let’s start with a factorial function:

float fat( float x )

{

float res = 1.0f;

while ( x > 1.0 )

{

res *= x;

x -= 1.0;

}

return res;

}

Generate the AST by piping the parser’s output to dot:

$ java -cp . Main test.sc | dot -Tpng > fat_ast.png

This gives us the following image:

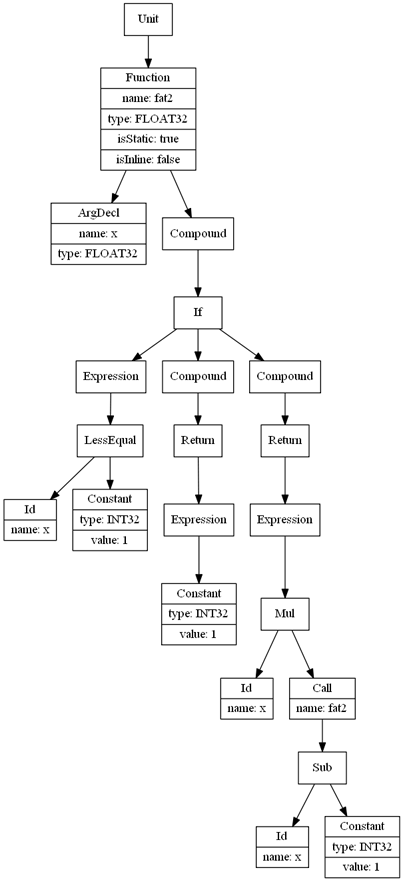

Now lets see the AST of the recursive factorial function:

static float fat2( float x )

{

if ( x <= 1.0 )

{

return 1.0;

}

else

{

return x * fat2( x - 1.0 );

}

}

Pretty neat, huh? We’ll use those a lot when the time for optimization and code generation comes.

Feedback From Part 1

On the comments section of my previous post someone said that if the hardware supports other data types he would like to have them available in SimpleC. I not only agree with him but I think that to achieve the goal of having a auto-vectorizing tool we must have support for all data types, otherwise its usage would be severely limited.

Let focus on signed, 16-bit integers (int16_t) as the conclusions we draw for this data type will very likely apply to all other data types as well. The problem with int16_t’s is that a vector of them will hold eight values instead of four as is the case with 32-bit integers and floats. So how can we sum a vector of int32_t’s and int16_t’s together?

One way we can add them is by making vectors always hold four values independently of the data type. So int16_t’s would take 32 bits each and we could add the two vectors together. The upper 16 bits of each int16_t value would be extended to the value’s signal so they would really be 32-bit wide but the generated code would treat them as 16-bit integers when e.g. multiplying them.

One problem with this approach is when we have arrays of int16_t’s. We don’t really want to loose half of the memory for the arrays by having only four values in each vector. To address this problem I thought about adding a packed keyword to declare arguments and variables of vectors with eight 16-bit and 16 8-bit integers. So we would have these data types in SimpleC:

| Packed | Type | Width (bits) | Values per vector |

|---|---|---|---|

| char | 8 | 4 | |

| packed | char | 8 | 16 |

| short | 16 | 4 | |

| packed | short | 16 | 8 |

| int | 32 | 4 | |

| packed | int | 32 | 4 |

Now we only need some way to pack and unpack vectors to be able to mix integers of different widths in operations. I’ve come up with these language constructs:

pack< type >( v0, ... )- unpack< type, starting index >( v )`

pack would take the vectors inside the parenthesis and pack them together to form a vector of the type inside the angle brackets, and unpack would take values from the vector starting at the informed index and unpack them to form a vector of the informed type. For example:

short sum( packed short s, int i0, int i1 )

{

// Get the first four shorts from vector s

int s0 = unpack< int, 0 >( s );

// Get the last four shorts from vector s

int s1 = unpack< int, 4 >( s );

// Sum

int res0 = s0 + i0;

int res1 = s1 + i1;

// Pack the result

short res = pack< short >( res0, res1 );

return res

}

Of course pack and unpack would translate to byte-shuffling instructions but that’s what we would have to do anyway if we were to mix integers of different widths. So I’m planning on adding those to SimpleC after we have our first functional version.

‘Till Next Post!

In the next post we’ll add more semantic actions to the grammar. These actions will keep track of variables declared so the parser can error out if it finds duplicate identifiers and on other error conditions. So the series now become:

- Part 1 of n: SimpleC and Abstract Syntax Trees

- Part 2 of n: Construction of the AST

- Part 3 of n: Semantic validation of SimpleC

- Part 4 of n: Constant folding optimization

- Part 5 of n: Code generation

And now the mandatory questions:

- I don’t mind instantiating objects at will and using bad practices in general when writing Java code (it seems to be standard way to use the language in the IT world) but would you write things in some other way?

- What do you think of the

packandunpacklanguage constructs? Are there better ways to mix types of different widths?

See ya!

Back